The Virtue of a Sense of Humor: 18th Century Satire and the Art of Thomas Rowlandson

Satire is defined as the use of humor, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to expose people’s stupidity or vices, particularly in the context of contemporary politics and other topical issues and serves as a mirror of our society, culture, and the people in it. During the 18th and early 19th centuries, satire was widely used in literature and art. Authors like Henry Fielding, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and Jane Austen all employed satire to humorously point out the flaws and eccentricities of the times they lived in.

In 2015, The Queen’s Gallery staged an exhibition entitled: High Spirits: The Comic Art of Thomas Rowlandson. The exhibition explored the humorous and satirical artwork of Thomas Rowlandson and other 18th century caricaturists. Noted for his political satire and social observation, Rowlandson was a prolific artist and printmaker. He produced a large number of illustrations that appeared in contemporary novels, humorous books, and topographical works. Like many of his contemporaries, his caricatures were robust and bawdy and left little to the imagination.

A letter from HRH, The Duke of Edinburgh appeared in the catalogue produced for the exhibition. In this letter, HRH pointed out that not all artists have the appropriate sense of humor to illustrate humor, and many humorists lack artistic talents to do so, but caricaturists are in a class of their own, and Thomas Rowlandson was a leader of that class. As far as caricaturists are concerned, HRH pointed out that there are two sides to that art form – the caricaturist and the subject of his work. To be the subject of a caricaturist’s work, one needed a sense of humor. To that extent, the Duke observed that the subjects of Rowlandson’s cartoons needed a pretty robust sense of humor. The exhibition provided many examples of how Rowlandson employed the full vocabulary of satire to comment on the events and characters in the world around him.

Of the many illustrations that appeared in this exhibition, I have selected three to illustrate as wide a range as possible of the kind of satire employed by Rowlandson and his contemporaries to comment on the times in which they lived.

Fig. 1. Bookseller and Author attributed to Henry Wigstead, 1784

This illustration, the Bookseller and Author (Fig 1.), which is attributed to Henry Wigstead, Rowlandson’s friend and artistic ally, is a classic look at late 18th century life. The figure on the right appears to be an exasperated author who has received some negative feedback on his latest work from the bookseller in the middle. The other man in the corner is presumably a customer browsing the bookstore and perhaps listening to a conversation that should remain private. The difference in stature between the bookseller and author indicates who is in control of this conversation. The bookseller, who appears to be well-fed and prosperous, has a haughty facial expression. He has imparted negative feedback to authors in the past and doesn’t care about the author’s feelings. The author, in contrast, is hunched over with his hat tucked under his arm in a much more defensive position. One can feel the anger that the author feels about the negative critique of his work. The brilliance and humor of this piece lies in the easy to imagine conversation with verbal humor akin to the best works of Oliver Goldsmith.

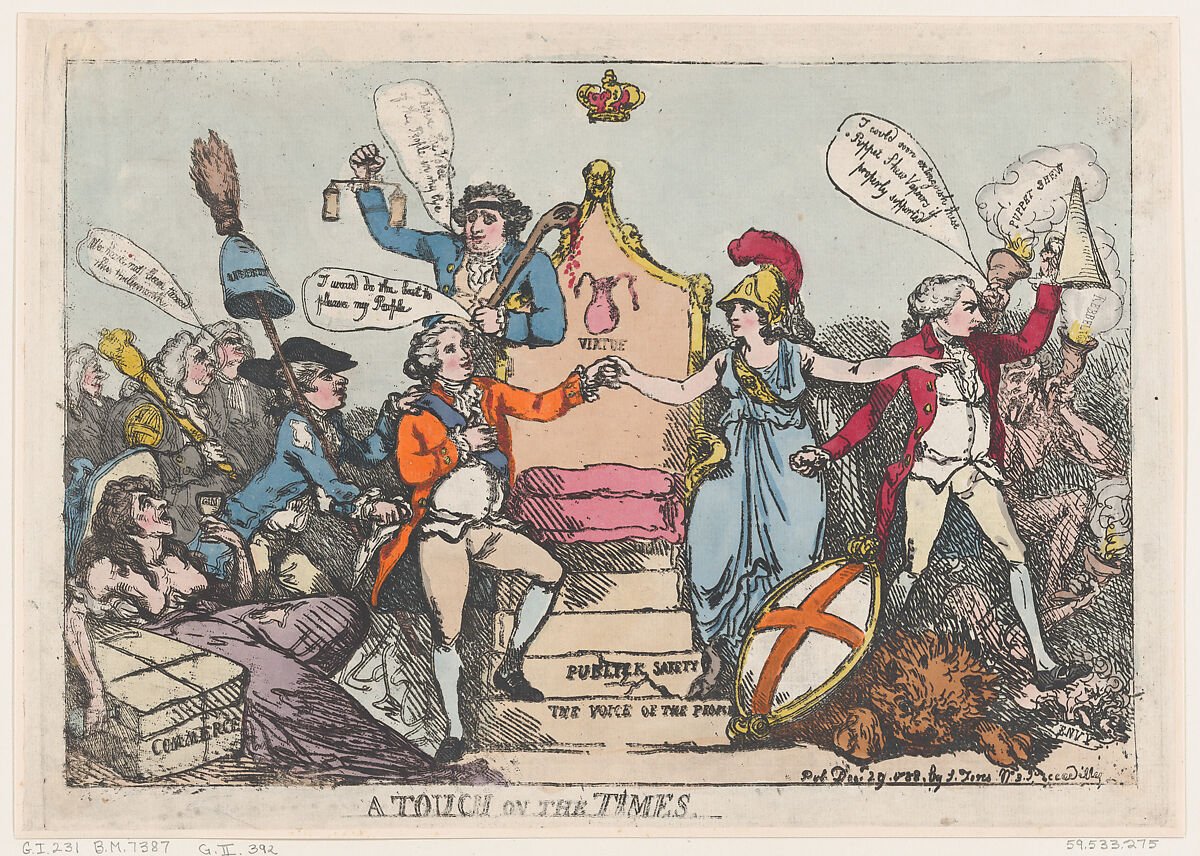

Fig. 2. A Touch on the Times by Thomas Rowlandson, 1788

At the height of the Regency Crisis of 1788, there was much uncertainty about the suitability of the Prince of Wales, the future King George IV, to be king. Rowlandson adds to the debate with A Touch on the Times (Fig. 2) using symbolism and “speech balloons”, akin to those used in comics, to make his points. The illustration is focused on the Prince walking up to a cracked and damaged throne with the assistance of a hooved Britannia. Fox, a supporter of the Prince Regent is depicted holding dice boxes and a cudgel in place of Liberty and Justice. The perception of the failing values that have been the foundations of Britain appear to be broken and on the verge of collapse. The removal of Liberty, the corruption of commerce, and the fires of rebellion all threaten the throne of virtue. William Pitt, bitterly opposed to the Regency and Fox, is seen attempting to put out the fires that threaten the throne. The key success behind this piece is Rowlandson’s ability to use the symbols of state and the people to show the danger of the times they were living in. The haggard looks of commerce and the other background caricatures shows the differentiation in the style of the individual figures. Yet, there is consistency in Rowlandson’s use of defined lines and colors in the foreground, allowing the viewer to understand the contrasting ideas and complexities of the situation he is trying to get across.

Fig. 3. Doctor Convex and Lady Concave by Thomas Rowlandson, 1802

Rowlandson’s Doctor Convex and Lady Concave (Fig. 3) is an example of the use of satire based on appearance rather than a laughable situation. The comedy of these two caricatures comes in the form of their physical shape and social status. The Doctor, of a lower social class, is large and physically invading the space of the lady. The Lady is thin and wiry and a representation of the upper class. Yet, despite their differences they are drawn together with their hands close to each other. This perceived intimacy, along with the entire shape of the rest of their bodies, may be Rowlandson’s way to joke about a certain level of sexual intercourse between the two caricatures. The quote at the bottom of the print, from the famous Elizabethan courtier Fulkes Greville, tells the viewer that it is appropriate for them to laugh at this illustration, for that is the power of satire to give people a moment of humor amongst the many tribulations of life.

High Spirits: The Comic Art of Thomas Rowlandson was a triumph of an exhibition that showed the work of a man who captured the events and feelings of the time period in which he lived through character, humor, and satire. He succeeded as all great artists do by displaying his work “not as a gentleman who gives a private or eleemosynary treat, but rather as one who keeps a public ordinary, at which all persons are welcome for their money” (Henry Fielding, The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling).

-Altalena